The Spark: Fluency Practice in a High School Classroom

Before the blow of pandemic-related learning loss, two-thirds of US high school students read below grade level, unable to read the complex text demanded in their English, science, and history classes. Because states paused testing during the pandemic, we don’t yet know how much bigger that number of struggling readers has become.

But we do know that the inability to read complex text is the greatest barrier to student success and engagement in high school. Teachers and administrators are under enormous pressure to jump-start students’ reading skills to enable them to tackle the longer sentences and unfamiliar vocabulary found in high school texts.

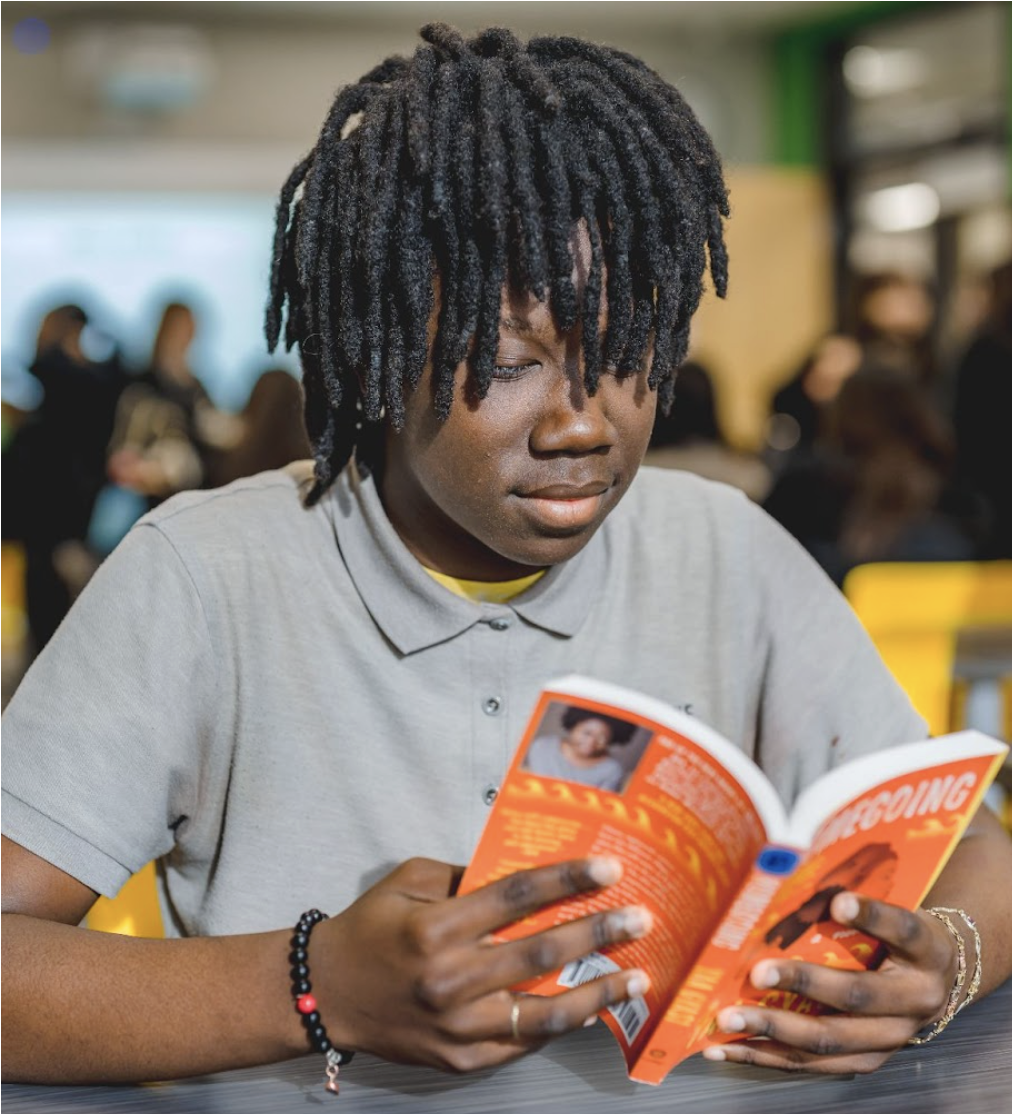

For the past 15 years, adolescent literacy research has pointed to systematic and repeated fluency practice (reading aloud with flow and expression) as the key to unlocking a student’s potential to read complex text. When students practice fluency, they hear a passage read by a strong reader and then receive guidance as they practice reading that passage aloud. Through these repeated experiences with different examples of longer sentences, students internalize the way that complex text works, understanding how certain clauses advance an author’s meaning in precise ways.

That means that if high school students engage in systematic and sustained fluency practice with grade-level texts, they can grow from a 4th grade reading level to a 9th grade reading level within a few months. Once students are fluent, they put their energy into comprehending and interpreting the text, appreciating the plot’s twists and turns, the characters’ motivations, and exciting new knowledge about the world.

If that’s really true, you might wonder, why do we have a reading crisis? High school students, unfortunately, typically do not practice fluency. When teachers try to monitor adolescents’ fluency, they typically use an approach copied from elementary classrooms with the teacher sitting beside the students and giving them 60 seconds to read as many words as possible while marking them down for mistakes.

This approach doesn’t work for high school students, high school teachers, or high school text. Adolescents hate being told to hurry and resent when the teacher points out their mistakes. Most high school students will refuse to read aloud under those conditions. High school teachers see at least 80 students per day and sometimes as many as 175. They don’t have time to sit down with every student and give them enough time to practice and improve. And complex text demands a more nuanced approach to reading aloud.

Readers of complex text need to notice and respond to the sentence structure, slowing down and speeding up to reflect the author’s meaning. When reading complex text aloud, good readers change intonation as longer clauses and more sophisticated vocabulary express a wide range of emotions and increasingly complex bits of knowledge.

By considering the strengths of adolescents, their playfulness and expressiveness, Riveting Results has developed an approach to fluency practice that enables any teacher to give all of her students as much practice as they need to read at grade level.

Over the next two weeks, I will be sharing my observations of how that approach worked in a summer school classroom of struggling students.

We want to know what you think.

We recommend you read these next

Meet The Team

The Riveting Results program works because it incorporates feedback from dozens of educators experienced in the classroom and in running schools. Unlike other programs that primarily use academic experts to review materials, Riveting Results gets feedback from educators who have actually used Riveting Results in the classroom to develop students reading and writing performance.

contact us